The Extreme Claim of Moral Philosophy

The Survival of the Self is an Illusion, In Between Every Thought is a Death

Derek Parfit is widely considered one of the most important and influential moral philosophers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. “He has written two books, both of which have been called the most important works to be written in the field [of moral philosophy] in more than a century.”[1] In Reasons and Persons, Derek Parfit brought up the possibility that “My relation to my Replica gives me no reason for special concern. Since ordinary survival is no better, it too gives me no such reason.” He called this the Extreme Claim, though he did say it could be defensibly denied. But that is exactly what these fourteen pages are going to argue. That it is rational to replace self-concern with an even handed concern for all present and future persons.

The extreme claim can also be rephrased as “the survival of the self is an illusion.” Maybe the idea that the self is an illusion is familiar from hearing about it from Buddhism or philosophy. But this article will take a look at the concept from a different direction by examining the science of the brain and the self, which is a little harder to brush aside than just philosophy or Buddhism. The more conventional concepts of no-self usually have to do with the idea of free will or some abstract idea of self. These ideas are fascinating to think about, but I think they are hard to apply to real life. To contrast, this will explain an idea that brings the concept of no-self into how we should honestly look at our future and past. But first, let’s define the self.

What is a Self

The word self is sometimes used interchangeably with personality, individual, or consciousness. These terms can easily confuse when not specifically defined. The word consciousness is so confusing in particular that George Miller, one of the founders of cognitive psychology said “Maybe we should ban the word for a decade or two until we can develop more precise terms” -Psychology: The Science of Mental Life

The same can be said to a lesser extent for the word “self.” But here is my simple definition. Self is commonly defined as “A person’s essential being that distinguishes them from others.” And the best way I’ve found to distinguish yourself from others is one simple criteria. Whether or not you anticipate experiencing their future. It is as simple as that, if you feel that you have or are going to experience what they feel and think, then they are you, you are the same self. Anticipation of future experience, an excellent phrase that cuts through the murkiness of talking about a self.

Now before we get any more abstract, it will be good to ground this idea of anticipation of future experience with a thought experiment.

Teleportation

Imagine you had a better travel option than flying in an airplane. Instead of going through all the hassle of a flight, the waiting, the lack of any legroom, the person who is being rude to the parent with the crying baby, you could just teleport to your destination. You would walk into a machine, get disassembled, and then reassembled across the globe in a fraction of a second.

Sounds great, right? Maybe not? If you think about the three steps it gets a bit trickier.

1.Scan

The teleporter scans your body with some ultra high-res MRI scanner, recording the exact location of every cell, every neuron firing in your brain.

2.Disassembly

You are disassembled instantaneously.

3.Reassembly

All of that information is sent to your destination, where it is used to assemble you out of new molecules using some ultra futuristic 3d printer. So when you arrive you are finishing the thought you started when you were scanned.

But what if step two doesn’t happen? What if the machine still reassembles you at the destination, but doesn’t disassemble you first.

You’d be standing there looking at the person you were expecting to have the experiences of. But you aren’t, you are still experiencing your point of view and not theirs.

You can’t be in two places at once. In fact you can’t be reassembled after being disassembled. When you don’t separate out the steps it seemed to make sense to anticipate being the teleported person. The teleported person would think they were you, your friends and family wouldn’t notice any change in your behavior after being teleported. But looking closely it becomes obvious that the anticipation was wrong. It seemed like you were being teleported, but in fact you were just being disassembled and a clone was created at the destination. A low budget teleportation service could cut corners by just killing the original instead of wasting money disassembling them atom by atom.

What is missing from the clone that would make your anticipation of having their experiences correct? You might respond, “it’s obvious, it’s my brain, not a clone’s.” But let’s slow down again and take a closer look at the steps. Instead of looking at the steps of teleportation. Let’s look at the evolutionary steps it took to create the self.

Evolution of the Self

For centuries people have assumed the self resides somewhere in the brain. With the discovery of evolution, this idea has progressed. Now it’s commonly believed that what started as a less advanced sense of self in primates evolved into its current form in humans. Evolution moves in small gradual steps. And if you look at the gradual steps it took to make the memory systems that the self emerges from you can see how our expectations were mistaken, just like in the teleporter example.

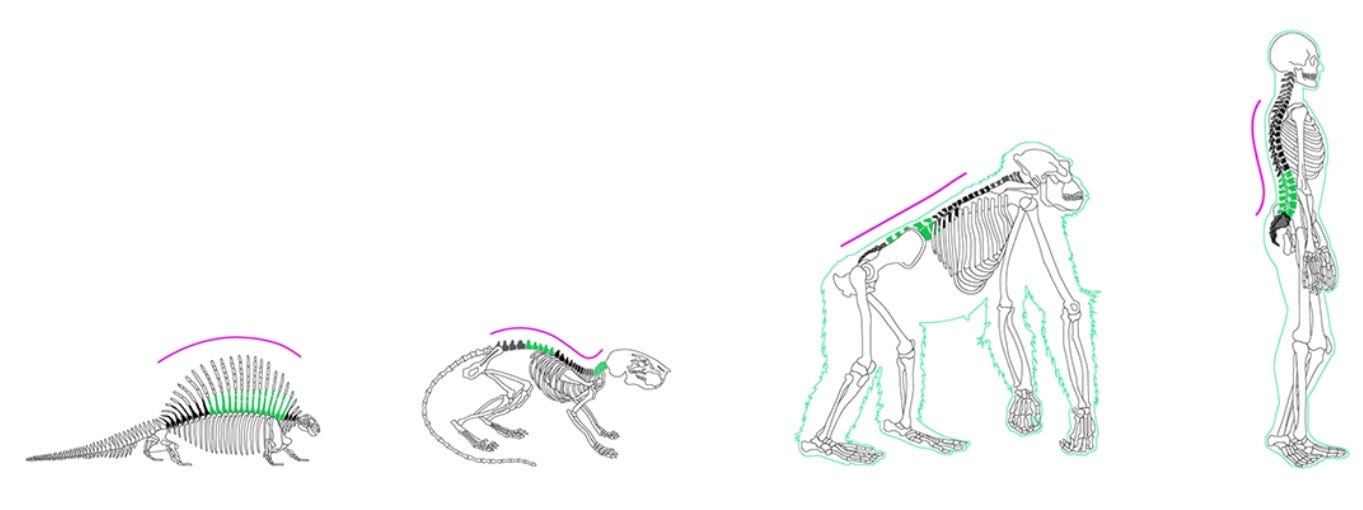

Here is a diagram of the evolution of humans going back to early vertebrates. At the bottom in red are the different memory systems and when they evolved.

So the parts of the brain that this feeling of self interest relies on weren’t created all at once the day Humans evolved from our previous ancestor species. It is the combination of many memory systems that evolved millions of years apart. This is called the Evolution Accretion Model of memory, described fantastically by Graham, Murray, and Wise in their book The Evolution of Memory Systems.

Evolution of the Self: Body Ownership

Starting at the beginning, memory systems emerged when the brain first evolved. Brains evolved for a seemingly simple reason, to move the body. There are animals called sea squirts that start out life as a tadpole, with a brain. Then they swim to find a good spot, plant themselves down permanently, and then eat their brain. They don’t need to move from that spot for the rest of their lives so no more need for a brain.

Brains allow for movement because they mentally represent where the boundary of the body is. The brain created a mental model of how the body is shaped so it can move accurately. When the body is attacked from the left it knows to swim to the right. This bodily awareness was the beginning of mental self interest.

“Brains evolved as a way of processing the external world and then interpreting that and generating internal models so that you can navigate around the world” -Prof. Bruce Hood.

After the brain learned to move its body it developed all the other memory systems, each of them reinforcing self interest. Eventually this self interest evolved into Explicit memories in humans.

Evolution of the Self: Explicit Memory

Explicit memories are memories that are accompanied by the feeling of participating or knowing. Explicit memory emerged out of the combination of existing memory systems. Memories of events, like a sunset, combined with mental images of selves to create a new dimension to memories. This dimension adds the perception of re-experiencing events when remembering them.

These different memory systems combine together to create human memory, and none of the systems “evolved in a [deliberate] pursuit of explicit memory; they provided advantages to some ancestral species in their time and place.” -The Evolution of Memory Systems

Explicit memory evolved when humans had to adapt to complex social groups. They benefited from modeling how they should act towards others since it increased their chance of survival in those social groups. So in their heads they developed more complex models of themselves and others so they could accurately predict how people would act.

And our models of selves aren’t perfect. The teleporter thought experiment is a good example. Our models initially allowed us to extend anticipation of future experience to the teleported clone.

It is understandable to think that explicit memory evolved to function just as it seems. That we have this feeling we experienced the past simply because we did. But “Evolution doesn’t act to yield perfection. It acts to yield function” -Anthropologist Matt Cartmill of Boston University.

In the next sections I will explain two other ways humans evolved imperfectly, before returning to the idea that explicit memory evolved imperfectly as well.

Imperfect Evolution: Spines

Our spines are good examples of how evolution only works in gradual steps, unable to discard vital systems to make entirely new ones. Humans have increased back pain because we weren’t able to evolve a new vertical spine, we gradually had to adapt our horizontal spine to become vertical. What was originally used as a bridge is now used as a skyscraper. The design of the human spine was selected for function using the parts we already had. We couldn’t evolve new spines. So we are stuck with these repurposed skeletons that aren’t good for pain-free long term use. They seem to break down right after the warranty is up.

Spines illustrate how evolution makes physical imperfections, but there are also mental imperfections. Optical illusions are a great way of experiencing our imperfect mental models.

Imperfect Evolution: Optical Illusions

One example of our imperfect mental models are the blind spots in our eyes. They aren’t noticeable usually since one eye fills in the gap for the other when they are both open. Close your left eye and look at the cross. If you start with your face close to the screen and then slowly move away from the screen the dot will disappear at the right distance.

This optical illusion happens because each of your eyes contains an area that has no photoreceptors because that spot is occupied by the optic nerve. Another example of evolution’s imperfect design. The early design gave an advantage and soon after that it was impossible to start over and make a correction. You got to work with the eye that you have. The only way evolution moves forward is through random mutations, not by reinventing things.

This optical illusion not only shows an imperfection in the function of our eyes, but also in our brains. That’s why the X disappears instead of us seeing an empty black spot in our vision when we close one eye.

Optical Illusions like these are examples of nonconscious processing. Or mental work that is being done without us being aware of it. Our eyes are taking in input and changing how we perceive it without us being aware of the change.

But that’s not all our brains do to compensate for our blind spots. They don’t just make isolated things disappear, they also fill in gaps in a pattern. Try this version of the optical illusion. Close your left eye and look at the cross again. This time the red X will go away but you won’t still see the break in the line. You’ll see a straight unbroken line.

So evolution dealt with a blind spot by assuming what is inside of that area is consistent with the area around it. If there is a line on either side, it probably continues through the blind spot. If there is something with a break in the middle that is small enough and in the right spot, we get an illusion of continuity.

This shows how evolution produced a brain that allows for the best function of the eye, not a brain that most factually represents reality. It would be annoying and dangerously distracting if we could see our blind spots. Imagine searching for prey and having two black spots always in the corner of your eye. If our brains were naturally selected to show us the truth, then we would see through the optical illusions. But thankfully they lie to us.

Imperfect Evolution: Explicit Memory

Our memory systems adapted in this imperfect way also. In a much more complex way our explicit memory is like the optical illusion. Our brains fill in the blanks between separate conscious experiences and give us the impression that we are one connected experience, just like how blind spots are filled in and show a connected line instead. Our vision wasn’t naturally selected to bring us closer to the truth and neither was our Explicit Memory. If it was, our perception of how our brains function would match up more with reality.

Our mental models aren’t perfect because they are the result of evolution, not deliberate design. Evolution doesn’t work in giant leaps, only gradual steps. Slowly multiple memory systems combined to create this perception of having experienced the past. An entirely new form of experience didn’t evolve in humans, we didn’t stop using entire parts of our brain because a human part appeared. Our brains just adapted the old forms of brain function that our ancestors had. It would be a large jump to create a persistent self that actually experiences all these moments, but it would be a small jump in evolution for the brain to create merely a perception of a self.

When you look at all the steps it took to give us the feeling of being a self you can’t find the step when an actual self was created. It wasn’t created with the early humans, or early mammals, or even early vertebrates. Once you choose a spot and claim it was created then, you can always argue that if that species had a self, then so did the species before it. We can’t find when it was created because it never was. The only thing created was the perception of the self. Which slowly grew out of earlier memory systems into the thoroughly convincing illusion we have as humans with our explicit memory.

Cognitive Psychology is pointing away from the idea of a central permanent self that governs the actions of a person. This idea is explained brilliantly and in clear language in Michael Gazzaniga’s book The Consciousness Instinct.

He talks about seeing brain damaged patients that can understand sentences, but can’t speak in sentences. There are some people with certain brain lesions who specifically can’t recognize fruit. Or a patient that had an iron rod go through their head and survived. They were able to do all the mental tasks they could before, just now their personality had changed.

“There are a tremendous number of brain lesion cases that paint a similar picture: Damage or dysfunction in brain region X causes a change in behavior Y, but consciousness almost always remains intact.”

“What we have learned from visiting the neurology clinic is that severe brain damage across various locations of the brain cannot stamp out consciousness per se. Certain contents of conscious experience may be lost, but not consciousness itself. This fact suggests that there is not a specific “Grand Central” cortical circuit that produces consciousness”

“That doesn’t mean there isn’t in fact some “essence” that is responsible, it’s just distributed. It’s in the protocols, the rules, the algorithms, the software. It’s how cells, ant hills, Internets, armies, brains, really work. It’s difficult for us because it doesn’t reside in some box somewhere, indeed it would be a design flaw if it did because that box would be a single point of failure. It’s, in fact, important that it not be in the modules but in the rules that they must obey.”

This is what leads me to think we don’t actually experience more than a fleeting moment of consciousness. Human consciousness is actually many separate experiences that feel connected because when we recall past events we innately feel we were there when they happened. Your brain remembers a past experience and instead of representing them as coming from a different experiencer your brain makes it seem connected, like in the optical illusion.

You feel connected to past experiences by your memory, but so would a teleported clone. I would argue both you and the teleported clone have essentially the same connection to those past experiences, and the same connection to anyone else’s past experiences. As I mentioned earlier Derek Parfit called this the Extreme Claim, “we have no reason to be concerned about [only] our own futures.”

A big part of the reason I’m writing this is to hear evidence against the extreme claim, especially in light of the Evolution Accretion Model. I know it is a ridiculous sounding claim, I’m frequently questioning it myself and would be very open to changing my mind if provided with new evidence. Please comment below with any you can think of.

I could go on and on about the neuroscience argument for the extreme claim, and I probably will in another article. But maybe some are hesitant to even consider the idea since it seems like it would lead you towards nihilism. The next section of the article should reassure you against that idea. In it, I transition away from explaining the argument for the extreme claim to answering the question “what are we supposed to do about it?”

No-self Help

This claim might be scary to people, it was to me initially. Is accepting this going to make me a walking zombie? Without any worry about the future? Will life lose its meaning? No, “a beautiful rainbow continues to be a beautiful rainbow even after it has been explained in terms of electromagnetic radiation.” That’s a quote from the philosopher Thomas Metzinger in his book The Ego Tunnel.

I imagine the extreme claim creates a similar fear to the fear people who lose faith in god have. You might think that without god as your moral guide you would become an immoral psychopath. In the same way, since the self is so central to how you understand your life it’s hard to imagine what would motivate you without it.

But for some people the realization of the illusion of the self isn’t distressing at all, in fact it is freeing.

“My life seemed like a glass tunnel, through which I was moving faster every year, and at the end of which there was darkness... [However] when I changed my view, the walls of my glass tunnel disappeared. I now live in the open air. There is still a difference between my life and the lives of other people. But the difference is less. Other people are closer. I am less concerned about the rest of my own life, and more concerned about the lives of others.” -Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons

The way I phrase it is a bit different because of my morbid sense of humor. There’s much less of a reason to fear death, I’ve already “died” multiple times today.

So it turned out you don’t lose all self control after accepting the extreme claim. In retrospect it seems like a silly thing to be afraid of. Like being afraid to accept hunger is just electrical signals coming from your stomach for fear of losing your appetite forever. It’s the same with the self, knowing that its connectedness is an illusion doesn’t make you selfless and uncaring. This feeling of being a continuing self is as hardwired as hunger. We can accept that the self is here to stay, but we can still change how we think about it.

Just like how even though we are aware the disappearing X is an optical illusion, it doesn’t change our perception of it. We can’t will ourselves into seeing the blind spot. Neither can we will ourselves to completely give up the perception of a continuing self.

As my collaborator Gordon Cornwall says in his fantastic blog The Phantom Self, treat your self interest “like your appetites for food and sex, something that we can, when necessary, resist, channel, or redirect.” To this end I’ve found a couple useful ways to resist my unproductive feelings of self.

When I find myself cringing at an awkward memory from high school I find a little comfort in the extreme claim. I tell myself “stop dwelling on the mistakes of a kid, leave him alone.”

It also helps when thinking about the future gets you anxious. Instead of worrying about what is going to happen to “you,” it helps to realize “you” won’t be there to experience it. Instead view it as a very close friend is going to experience it. Not to say that you shouldn’t worry and plan for the future, or learn from the past, but the extreme claim lets you consider how to approach it more calmly.

Gordon also phrases it as a shift away from self interest, and instead towards sympathetic concern with your future selves and other selves. Since consciousness is just a momentary experience, you have just as much reason to want your future to be pleasant as your neighbor’s. You aren’t going to be experiencing either, but countless selves in the past worked to make your experience better today, pay it forward. Instead of taking this as just an excuse to be less empathetic to your future selves, use it to extend empathy to everyone’s future selves.

And if you get the chance to use a teleporter, why not?