Consciousness as government

Do you feel like you are controlling your brain? Governing it? If you had to compare your brain to a form of government would your consciousness be a dictatorship? Maybe a democracy? It might seem from the inside to be a dictatorship or a democracy at different times. When you have a reflex to catch a falling object it might seem like a quick acting and centralized dictatorship. But when you have to make a moral decision it might seem like a jury arguing about a murder trial. You have mixed feelings because different parts of you are pushing in different directions. But how it seems to us on the inside is different from how our brains actually work. When we look at the science of the brain, it is a lot different from how it feels. The best metaphor for how your brain is truly governed is no government at all. Our brains function much like anarchy.

Anarchy is not the same thing as chaos. The word anarchy doesn’t mean “no rules,” it means “no rulers.” This view of Anarchism as merely chaos mirrors the early and also incorrect theory of neuroscience called Equipotential. This is the idea that in humans “any part of the brain can carry out a given task, thus no specialization… At the time it was thought that ‘anything went’ in the nervous system, there was no structured system.” [1] In the same way a common misconception of Anarchism is that anything goes. But the truth is that Anarchists aren’t against rules, they are just against laws imposed from the top-down.

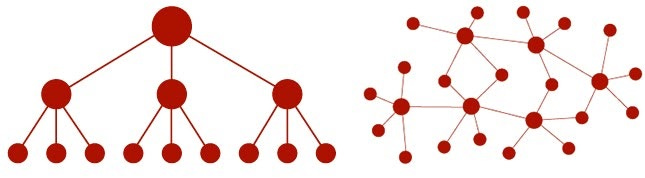

Centralized Organization vs Decentralized Organization

If anarchy is a new subject for you and you are curious enough to get a better understanding before continuing with this article I’d recommend this page from the website TV Tropes. It is a fun pop culture wiki for plot devices, but has a surprisingly good introduction for anarchism. Or if you have a specific question like, “Aren’t people naturally competitive?”, “What’s to stop someone from killing people?”, or “Who will take out the trash?” then check out anarchy.works.

I will eventually explain why consciousness doesn’t feel like anarchy. But in the next section I will explain why anarchy is the best metaphor for how our brains are organized.

How is Consciousness like Anarchy?

Michael Gazzaniga is a pioneering researcher in Cognitive Neuroscience. And he has described how the function of the brain is different from our expectations in his fantastic book Who’s in Charge: Free Will and the Science of the Brain. [1] Although Gazzaniga would probably take issue with the metaphor. He refers to the lack of a central hierarchy in the mind in much different terms. He calls the mind a “free market” and says it has “a diversified portfolio.” But in my opinion the way he describes it sounds like anarchy.

"We began to doubt that a single mechanism existed that enables conscious experience... we came to understand that consciousness is distributed everywhere across the brain... All these modules are not reporting to a department head, it is a free-for-all, self-organizing system… No central command center keeps all other brain systems hopping to the instructions of a five-star general… There is no one boss in the brain.” [1] Anarchism has a lot of similarities with this concept of the brain’s organization. Even if you aren’t familiar with anarchism, you can begin to see how consciousness is at least not like a dictatorship.

It would be understandable to assume that humans got to the top of the food chain because of our big brains. That humans gained intelligence by slowly evolving to have proportionally more neurons in the brain compared to other primates, but that’s not true. In the same way lots of people assume that more government control, and more cops are good solutions to societal problems. But evolution says otherwise. “The human brain is a proportionately scaled-up primate brain: It is what is expected for a primate of our size and does not possess relatively more neurons.” [1]

Humans didn’t evolve to have proportionally bigger brains or even more centralized organization, instead intelligence seems to come from more tightly knit local connections. This matches up with the anarchist principle of enabling local decisions to be the most important. “As primate brains have increased in size, however, the corpus callosum, the large neuronal fiber tract that transmits information between the two hemispheres of the brain, has become proportionately smaller. Increased brain size is thus associated with reduced interhemispheric communication. As we have evolved toward the human condition the two hemispheres have become less hooked up. Meanwhile, the amount of connectivity within each hemisphere, the number of local circuits, has increased, resulting in more local processing.” [1]

In this metaphor people are the individual neurons in the brain. In an anarchist society people can organize together into individual neighborhood assemblies called municipalities or communes. In a similar way groups of neurons assemble to make modules in the brain. A module is a local, specialized circuit for specific functions. “One part of the brain reacts when you hear words, another particular part of the brain reacts to seeing words, still another area reacts while speaking words, and they can all be going at the same time.” [1] Modules and municipalities can’t do much on their own, but working together they can do amazing things.

Blindsight is a phenomenon that perfectly illustrates how modules in the brain work. Blindsighted people can’t see but have perfectly functioning eyes. They aren’t aware of seeing anything but their mind still reacts to things it sees. To test this researchers filled a hallway with hazards but didn’t warn the blindsighted person before telling them to walk down it. They thought it was a normal hallway but the blindsighted person managed to avoid all of the hazards. At the end of the hallway, after brushing against a wall to get past a trash can, they asked him why he walked that way. He said he was just walking how he wanted to, not because anything was in the hallway. Blindsighted people are also able to detect color differences, brightness changes, different shapes, and can track movement. They can’t see, but some parts of their brain are still processing visual information. Sensory input is still going from the eye into the brain, but one of the modules near the end of the process is malfunctioning. The brain can still react to things it sees, but just isn’t consciously aware of seeing them.

You might respond to learning about modules by saying “but surely there is still a set of modules at the top that control the others.” Michael Gazzaniga’s decades of research say otherwise, “while hierarchical processing takes place within the modules, it is looking like there is no hierarchy among the modules.” [1]

While researching this topic I found a book all about comparing nervous systems to governments. Governing Behavior is written by Ari Berkowitz, a professor of Cellular & Behavioral Neurobiology. He describes specific functions of nervous systems as dictatorships or democracies but says “there does not need to be a single form of government” [6] for the entire nervous system. This is because “there are also important differences between the governments of animals and those of countries.” [2] And you’ll never guess what kind of organization those three differences actually describe.

“One difference is that nervous systems don’t follow a single playbook that is clearly laid out like a constitution and set of laws... Nervous systems use multiple playbooks, often at the same time... If a country’s government tries to simultaneously implement two competing mechanisms for decision making, there would be problems… But this is not the case in nervous systems. Somehow, nervous systems are able to implement distinct architectures of government simultaneously without problematic conflicts... How is this possible?... Nervous systems have evolved over long periods of time to govern behaviors in whichever ways are effective, building on whatever previous forms of government existed... It may be that competing mechanisms can coexist in nervous systems because the goal of an animal is not to implement one particular governing structure; the goal is to produce the best available behavior.” [2]

This is also the goal of an anarchist society. Anarchists don’t want people to just conform to a rigid set of ideas of what society should be. They want everyone to get involved in figuring out how we can organize together in the society we have right now. Local groups decide how things work for themselves and so anarchist societies end up with many different playbooks. By looking at anarchism as a diverse method instead of as a strict ideology people are able to improve existing conditions instead of trying to change them into something specific. As Ashanti Alston said, "One of the most important lessons learned from anarchism is that you need to look for the radical things that we already do and try to encourage them." And radical in this sense doesn’t mean extreme, “Radical simply means "grasping things at the root.” -Angela Davis

“A second difference between countries’ governments and nervous systems may be the capacity nervous systems have for immediate and autonomous self-correction.” [2] Peter Kropotkin compared this flexibility of organic life to an anarchist society. “Such a society would represent nothing immutable. On the contrary - as is seen in organic life at large - harmony would result from an ever-changing adjustment and readjustment of equilibrium between the multitudes of forces and influences, and this adjustment would be the easier to obtain as none of the forces would enjoy a special protection from the state.” [3] Peter Kropotkin became an anarchist partly due to his work as an evolutionary biologist.

“A third difference between countries’ governments and nervous systems may be the variety of ways in which different nervous systems are able to achieve the same goals approximately equally well.” [2]

This is a benefit of the flattening of organizations. Vertical organizations are good for quick top-down decision making. But aren't good when one part of the chain breaks. To contrast, horizontal organizations are very resilient because they don’t have single points of failure. If one node is broken, there are other ways of getting the same thing done.

If there isn’t a central hierarchy in the brain, then why does it feel so convincingly like there is one? It’s because there is one very busy set of modules that makes it seem like we’re the dictators of our minds.

The Storyteller in the Brain: Why consciousness seems like a dictatorship

Gazzaniga and Sperry’s pioneering research in Cognitive Neuroscience illustrates why the mind doesn’t feel like anarchy. Their research involved split-brain patients. These people were suffering from such terrible seizures that they had brain surgery to disconnect the two hemispheres of their brain. The two hemispheres are connected by the Corpus Callosum, which is on top of the brain stem. The surgery cuts along the middle of the Corpus Callosum, essentially stopping all communication between the two hemispheres.

3d models from: Nevit Dilmen, Ziegler D, and Anguera R

Why would someone agree to this? Well it worked to get rid of the seizures and the recovered patients reported that the surgery was a success. They felt like the same person and verbal IQ and problem solving capacities remained the same . The two hemispheres are still connected by the brain stem but they can’t talk directly to each other. You’d think a major change to the brain like that would result in some other side effects besides reducing seizures. That’s why Gazzaniga and Sperry used some new testing equipment to investigate.

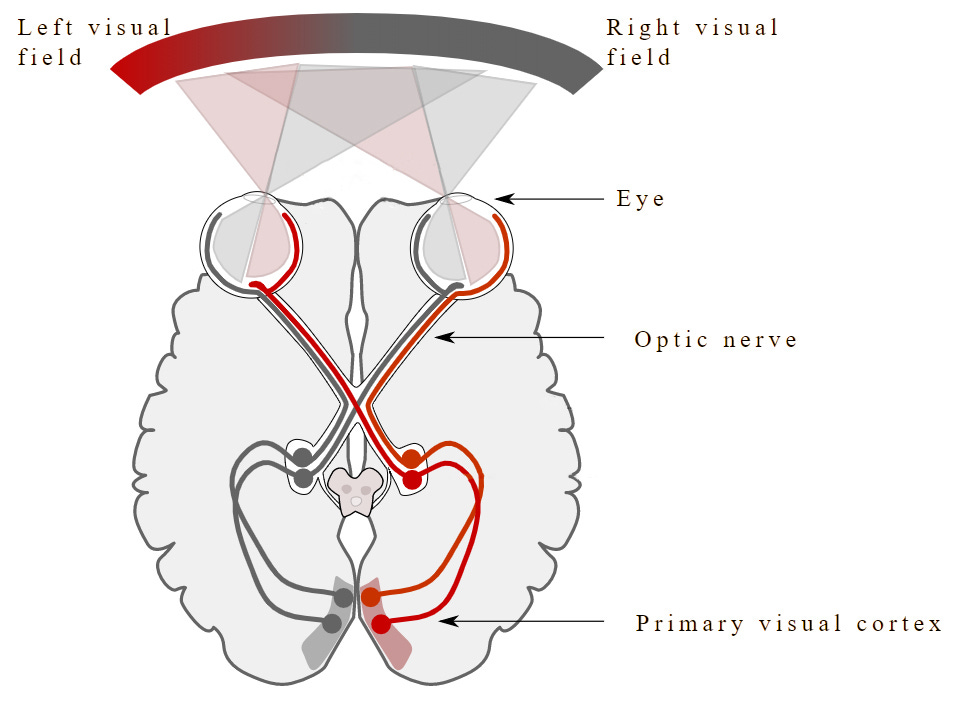

Oktar, Yigit & Karakaya, Diclehan & Ulucan, Oguzhan & Turkan, Mehmet. (2019). Convolutional Neural Networks: A Binocular Vision Perspective.

This testing equipment was designed to show the curious wiring set up of the brain. You might think everything seen by the eyes would be processed together but it isn’t. The left sides of both your eyes are processed together and the right sides of both your eyes are processed together but in the other hemisphere. And here’s the extra curious part, the left side of your vision, in fact the whole left side of your body, is actually processed in the right hemisphere and vice versa. So this allowed Gazzaniga and Sperry to talk to either the left or right hemisphere in these split-brain patients. They set up two screens on either side of the patient’s line of sight. That way when the patient looks at the dot in the center you can quickly show images on one screen that will only be seen by one hemisphere. So images on the left screen will only be seen by the right hemisphere.

They also set up two buzzers, one for each hand, like the hemispheres were competing on a game show. They flashed a light on the right side and just as you would expect the patient’s right hand pressed their buzzer and he said he saw the light. But something fascinating happened when they switched sides. They flashed a light on the left side and his left hand pressed their buzzer, but the patient said he didn’t see anything!

Each hemisphere can only see one screen. And both hemispheres can react intelligently to things the other isn’t conscious of. Only one hemisphere can talk but the shy hemisphere isn’t overall less intelligent. They just have a different set of modules. For instance the shy hemisphere has a module that “helps us understand the broader social meaning of the words that are said, such as whether someone is telling a joke versus being mean.” [5] So if your left hemisphere is told a joke making fun of the right hemisphere for supposedly being dumb, they might not even get the joke.

Gazzaniga, Michael S., "The Split Brain Revisited," Scientific American, July 1998

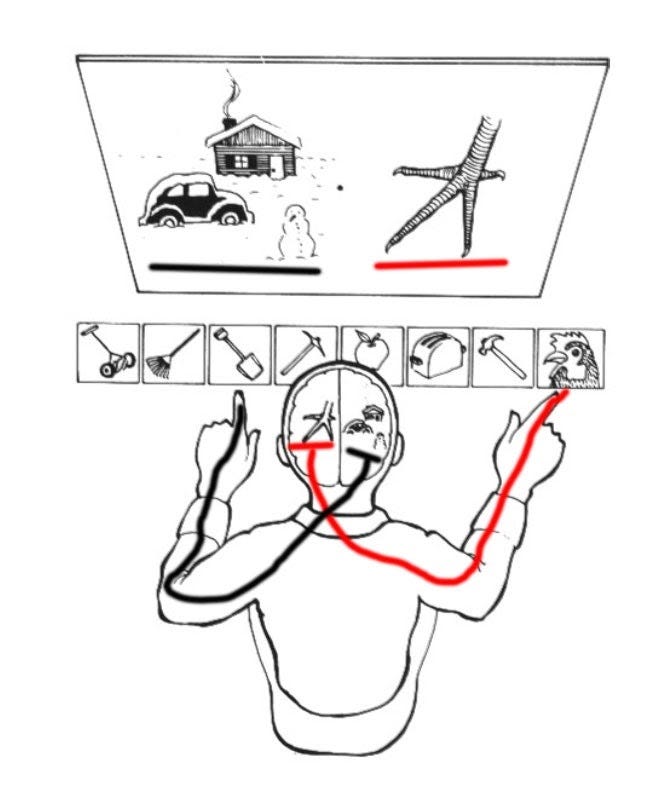

They continued the test by briefly showing an image of a chicken foot on the right and a snowy field on the left. They were then asked to point to the card that corresponded to the image on the screen. So with their right hand they pointed to “chicken” and with their left hand they pointed to “shovel.” Now maybe you would think the subject would say “I pointed to ‘chicken’ since I saw a chicken and I guess my other side saw a shovel.” But in fact the split brain patient felt like both actions were theirs. Instead of confusion about their other side pointing to the shovel they explained it away by saying, “And you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed.” “[The left hemisphere] knew nothing about the snow scene, but it had to explain the shovel in his left hand. Well, chickens do make a mess, and you have to clean it up. Ah, that’s it! Makes sense. What was interesting was that the left hemisphere did not say, “I don’t know,” which truly was the correct answer. It made up a post hoc answer that fit the situation. It confabulated, taking cues from what it knew and putting them together in an answer that made sense. We called this left-hemisphere process the interpreter.” [1]

Michael Gazzaniga calls this the interpreter module, but I prefer the storyteller module. Alternatively, to go along with the political metaphor of this essay, we could call it the propagandist module. Gazzaniga also switches between calling it the interpreter module, and the interpreter system. I believe “system” is more accurate since it is likely not just one module performing this complex behavior.

“The interpreter receives the results of the computations of a multitude of modules. It does not receive the information that there are multitudes of modules. It does not receive the information about how the modules work. It does not receive the information that there is a pattern-recognition system in the right hemisphere… It gets the gist of the situation from all the input, tries to find a pattern, and puts it together in a makes-sense interpretation… As you and I muddle through life, moving from one task to the next, different regions, distributed across the brain, come into play and are seamlessly blended together, dominating our consciousness from moment to moment… This is what our brain does all day long. It takes input from other areas of our brain and from the environment and synthesizes it into a story… That YOU that you are so proud of is a story woven together by your interpreter module to account for as much of your behavior as it can incorporate, and it denies or rationalizes the rest.” [1]

The storyteller system doesn’t only tell us stories about why the body does something, but also stories about why the brain feels something. Both hemispheres are still connected to a common brain stem so emotions are shared between them. “The interpreter is an extremely busy system. We found that it is even active in the emotional sphere, trying to explain mood shifts. In one of our patients, we triggered a negative mood in the right hemisphere by showing a scary fire safety video about a guy getting pushed into a fire. When asked what she saw, she said, “I don’t really know what I saw. I think just a white flash.” But when asked if it made her feel any emotion, she said, “I don’t really know why, but I’m kind of scared. I feel jumpy, I think maybe I don’t like this room, or maybe it’s you, you’re getting me nervous.” She then turned to one of the research assistants and said, “I know I like Dr. Gazzaniga, but right now I’m scared of him for some reason.” She felt the emotional response to the video—all the autonomic results—but had no idea what caused them. The left-brain interpreter had to explain why she felt scared.” [1]

This discovery of the separate cognition of both hemispheres wasn’t a complete surprise though. “When one split-brain patient dressed himself, he sometimes pulled his pants up with one hand (that side of his brain wanted to get dressed) and down with the other (this side did not). He also reported to have grabbed his wife with his left hand and shaken her violently, at which point his right hand came to her aid and grabbed the aggressive left hand. However, such conflicts are very rare. If a conflict arises, one hemisphere usually overrides the other.” [4] And because of the flexibility of the brain these conflicts only occur shortly after the surgery. Over time the hemispheres learn to work together and signal to each other in different ways. The right hemisphere can even learn to speak, but never as fluently as the left. It becomes like a game of 20 questions between the two hemispheres.

It’s hard to imagine how a split brain patient couldn’t immediately notice that they are only seeing half of what they used to. Here’s how Michael Gazzaniga explains it. “Right after split-brain surgery, when you ask a patient, “How are you?” The answer is “Fine.” Then you ask,” Do you notice anything different?” and the reply is “No.” How could this be? You must remember that as the patient is looking at you, he cannot describe anything in the left part of his visual field. The left hemisphere, which is telling you that all is fine, cannot see half of what is in front of him and is not concerned about it. To compensate for this when not under testing conditions, split-brain patients will unconsciously move their heads to input visual information to both hemispheres. If you woke up from most other types of surgery and couldn’t see anything in your left visual field, you would certainly be complaining about it, “Ahh, doc, I can’t see anything on the left—what’s up with that?” These patients never comment on this. Even after years of frequent testing, when asked if they know why they are being tested, they have no sense that they are special, no sense that anything is different about them or their brain. Their left brain does not miss their right brain or any of its functions. This has led us to realize that in order to be conscious about a particular part of space, the part of the cortex that processes that part of space is involved. If it is not functioning, then that part of space no longer exists for that brain or that person. If you are talking out of your left hemisphere, and I am asking you about your awareness of things in the left visual field, that processing is over in the disconnected right hemisphere and that hemisphere is conscious about it, but your left hemisphere is not. That area simply does not exist for the left hemisphere. It doesn’t miss what it doesn’t have processing for, just like you don’t miss some random person that you have never heard of.” [1]

This split brain experiment caused a lot of discussion. One popular question is, do the patients still have one mind? Or two? Maybe more? This is where the anarchy metaphor works well. The brain doesn’t become two separate minds after the surgery the same way that an anarchist society connected by a bridge doesn’t become two dictatorships after the bridge collapses. It was never one mind, at least in the way we were thinking about it. Split brain patients don’t have two minds, the main difference after the surgery is the storyteller system now has less information to work with, so the story is less convincing.

The propagandist in your head is very persistent. I don’t think there is a way to get rid of them. I just keep reminding myself that there isn’t a king in my head. It's always been just the cooperation of neurons that enabled this rich inner life to grow.

So this one set of modules is why we feel like a dictatorship inside of our anarchist mind. There is a propagandist explaining away all the variety of behavior as merely the will of our dear leader. And it makes sense that evolution would favor us thinking this way. If you think that all of your consciousness is unified then you will plan ahead and make sure your future will be pleasant. It is a very motivating and clear story. This story allowed us to survive and reproduce, and evolution reinforced that slowly over time.

Consciousness is Anarchy: Why use this metaphor?

This metaphor stood out to me since anarchy and neuroscience are both easily discounted by people in the same way. “How can there be order without something imposing it? Surely we need a unified source of authority?” Seems like what evolution decided we really needed was a clear story to understand and predict our world. We tell ourselves the story that we are in control of most if not all of our actions. Governments also tell us the story that they are in control of the fate of the country. Not to say that people don’t have responsibility for any of their actions, or that existing governments shouldn’t try to do anything. But by looking at people and governments from this perspective we can improve ourselves and our governments. Or evolve new organizations outside of governments that would eventually make governments as unnecessary as male nipples.

The conclusion that the brain doesn’t have a central command center can be very disorienting. If the stories our minds have written for themselves are wrong, what is the true story? How should we think about our sense of self? This is a difficult question to answer, I attempted to do so in my previous post. So I’d recommend checking that out if you are curious.

But let me try a simplified explanation using the anarchy metaphor. You might not be a dictator of your mind, but that doesn’t make you a serf or a citizen of a representative democracy. You can think of yourself as a member of the anarchist society of your mind. You can’t control society, but you do have a direct influence on how it functions.

This argument probably seems hard to swallow. It might seem disgraceful to accept that you are just groups of neurons fooling themselves. But there’s another option, here’s a Carl Sagan quote to end the essay with, “To me it is not in the least demeaning that consciousness and intelligence are the result of “mere” matter sufficiently complexly arranged; on the contrary, it is an exalting tribute to the subtlety of matter and the laws of Nature.”

The real question given the black and red is, how is communist dictatorship like anarchy